Radio Nowhere Development Diary

May 2024 - Ronan Jennings

Our second game, Radio Nowhere, has just opened! There was a lot of pressure to have a solid follow-up to our original game, and the fear of ‘Second Album Syndrome’ was strong. But if the first month’s worth of players are to be believed, I think we’ve pulled it off. The first thought of a second room started about a month after our original game opened, back in early 2023. We planned a big, spooky, monster hunting experience that would push the boundaries of escape room design in some new and crazy ways. That plan is still in the works, but the ambitions for it have… uhh… grown. So we’re going to come back to that project down the line when we can afford to give it the time and budget it deserves.The next thought came with the realisation that The Murder of Max Sinclair (then just called Case Closed) was quite light-weight as a game, at least in terms of the physical materials. Most of the game was briefcases and stacks of paper. And with the number of players we had saying that they wished they could just play it again, or solve a different case along the same lines, we started to think that maybe we could have two separate mysteries nestled inside the same room, where we could swap the materials back and forth with relative ease, doubling up the number of games we had running at once.The final product of Radio Nowhere ended up being much, much more ambitious than that, but that’s how it all got started. Originally it would be another noir mystery, with the theming and atmosphere much the same as Max Sinclair, until we thought that we might as well give it an identity of its own. Rather than moody detectives, we’d have groovy detectives. Rather than a dark, morally ambiguous story, we’d have a fun and over the top adventure. Rather than a grimy PI’s office, it should be a… hmmm… bar? Disco? Music studio? Radio station? Yes, radio station. Points to the video game Killer Frequency for helping to influence that decision. Max’s desk: Moody, minimalist.

Radio Nowhere’s DJ booth: Groovy, maximalist.

The Murder of Max Sinclair is a great mystery with twists and turns, but I wanted to have a crack at making a classic whodunnit. A game where you have a list of suspects, and it’s your job to narrow that list down until you have your culprit. That meant populating the radio station with characters, giving them all backstories and subplots, and their own mysteries to dig into.This was surprisingly difficult, probably because it was a while before we had the actual story nailed down. I won’t say what the actual plot is in case you haven’t played the game yet, but there was a point where we knew we had a murder in a radio station, but that was about it. Why are only the other employees suspects, and what was really going on here? Our games are narrative-based, so it wasn’t enough to just give someone a petty grudge and a gun to shoot with. The cause for the murder had to be woven throughout the entire plot, and foreshadowed in almost every element of the room. It had to involve multiple characters, and had to be internally consistent. In other words, it had to make sense.The tricky part about making games where you’re asking people to find things that are suspicious or don’t make sense, and to come up with their own theories is that you can’t rely on ‘Escape Room Logic’ to brush away the details that don’t quite work. Everything had to be watertight, nothing could be there “just cause it’s an escape room”.So we had an eight hour long meeting where we went through every possible character and every possible plot, and motivation, and secret conspiracy.

Some highlights of the bad ideas:-The villain would be someone called ‘Radio Everywhere’.

-There’s an evil Artificial Intelligence that runs the station (this could be Radio Everywhere?).

-The victim had a stalker, things would become darker and grimmer, and more along the lines of the Zodiac killer as you went along. Grim.

-The phrase “The radio host is the radio ghost”.

-A ghost?!? You’re being helped/haunted by the ghost of the murder victim.

-Karaoke!

-The plot revolving around the phrase “Too late bitches, time for bacon.”

Plus I just found one note that says: “Radio Bomb?”After losing our minds for an entire afternoon/evening, and being neck deep into the grim and gritty serial killer plot line, we stopped to get some food at a kebab shop round the corner. While we were waiting, the kebab shop had ‘Take on Me’ by A-Ha playing in the background. We all looked at each other and realised where we’d been going wrong. From there we nailed down the exact tone and figured out the broad strokes of the story, with all the finer details filling in naturally over the next couple weeks.“Okay, we’ve built a radio booth. Now what?”

Now those were all the bad and silly ideas that didn’t make it into the game, but that doesn’t mean there weren’t silly ideas that did make it into the game. Radio Nowhere was a big victim of Scope Creep, a concept where you start with a small idea for a project, but the scope of it grows and grows until it becomes much more work than you’d originally planned for. There were loads of pretty huge elements of the game that started as “Hey wouldn’t it be funny if…”, which became “That’d be great, shame it’s impossible”, which became “I think I’ve figured it out. Give me three weeks, I need to learn Unreal Engine from scratch.” An actually functioning Radio Station, a detailed Police Database, a voice controlled CCTV Monitoring minigame, and a couple other big things I won’t spoil here. These are all things that would have been the big centrepiece of any other room, but ended up as just another thing to add to the list, and another new skill we needed to learn from scratch in order to build. There were definitely a few Sunk Cost Fallacy moments where something just wasn’t working, but we’d spent weeks putting it together and refused to give up. These were usually solved by aggressive playtesting, long nights of coding, and in one extreme example: Buying a brand new laptop in a massive panic two days before the game went live.

With so many new ideas, of course it didn't all go to plan straight away. We have a “test early, test often” approach to game design. This means we can catch issues early, and iterate through a few different concepts while the game’s still made from scraps of paper and hand-drawn pictures scattered around my living room. We did some experimental things with this game - not just with the crazy ideas listed above, but with the basics of how escape room gameflow works as well - like having diverging puzzle paths depending on which suspects you choose, and writing your theories on forms instead of entering numbers in padlocks. It was important to see if these things worked, and how we could fix them if they didn’t.Usually, on first attempt, they didn’t. The diverging puzzle paths was an issue, because we had to make the story make sense no matter which route players took. We had to think of the story from four different angles, and had to make double the number of puzzles. Early attempts at this were… mediocre. The characters were inconsistent, and the puzzles were bland. In one play test we realised we’d been too hesitant to give incriminating evidence about the true culprit, so the middle section of the game was sorely lacking in shocking revelations. So that had to get reworked and restructured, until all of the suspects had their own interesting stories going on, while not distracting from the mystery at hand.My first sketch of the game flow, many months before we started building. Some ideas changed, but a few core concepts never budged.

One of our big “Wouldn’t it be funny” ideas was to have the players actually host their own radio station, with a live listener count based on how well they’re doing. This ended up being a cornerstone of the game, but was very difficult to make work.Early playtesters always started off hosting their show with enthusiasm, before quickly focusing on the puzzles and forgetting that the radio existed. It’s one thing to give players a sandbox, but it’s another to give them goals, challenges, and rewards for how they play. We learned that providing constant feedback to the players was crucially important. Introduce a song? Listener numbers go up. Play some good music? You get fan mail. If there’s a bit of dead air, the producer suggests they read some news, do an ad, or conduct an interview.In these early tests, we were relying too much on the radio being intrinsically satisfying to play with, but if players weren’t getting rewarded with compliments, extra listeners, and new content, they quickly lost interest. The most economic way of getting cassette tapes was to bulk-buy collections of totally random sets. These were the “good” ones, after some curation. We’ve made some more edits as we’ve gone along.

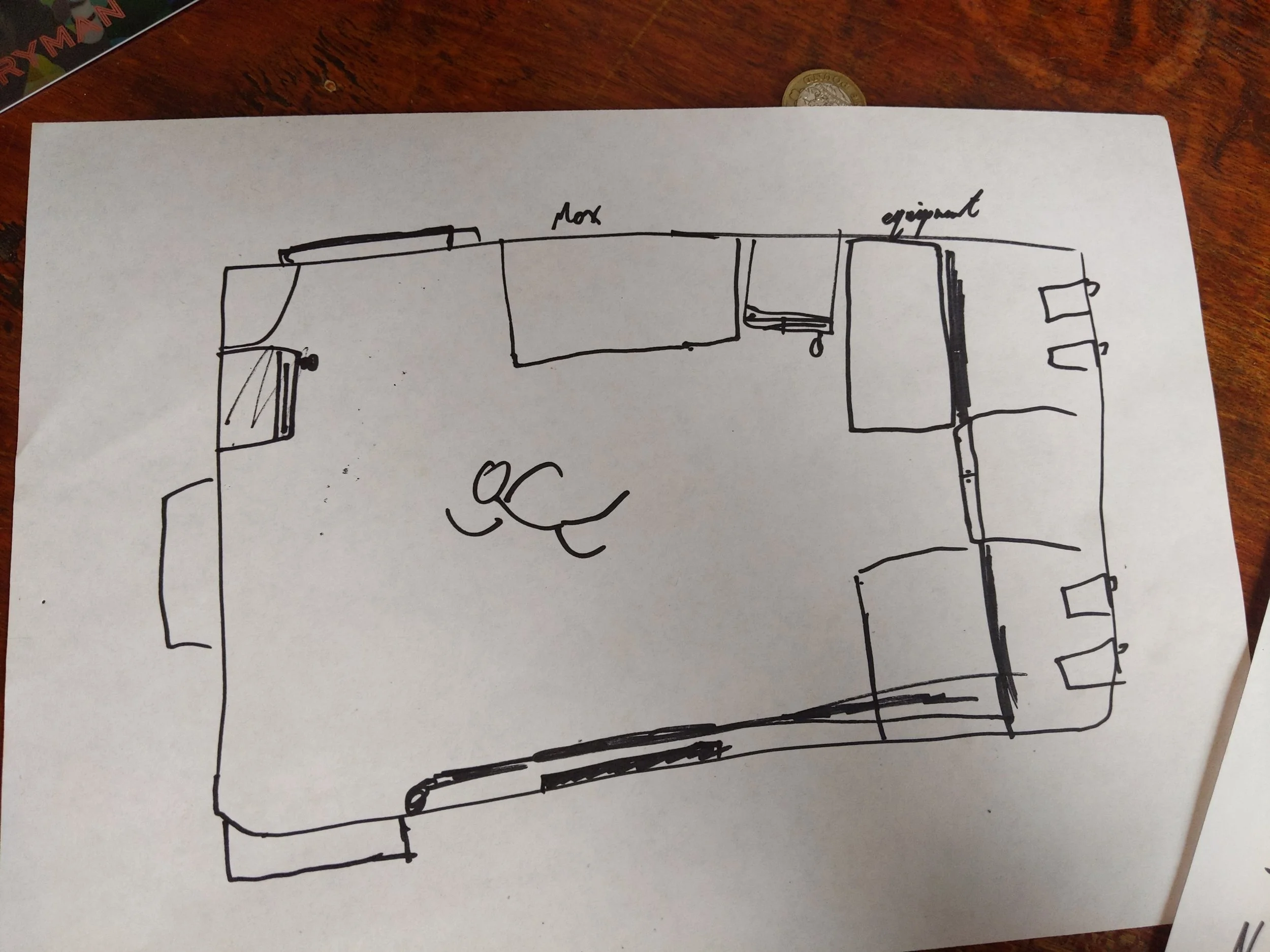

There were also issues we didn’t expect, like how many cassette tapes is too many? At first we thought that wouldn’t be a problem, until the sheer volume of them became a distraction, even an annoyance. So we cut back, and carefully positioned the ones we kept. Rather than 40 tapes of music to choose from at the beginning of the game, now there are only 2. Do a bit of digging and you’ll very quickly find 3 more, with more being trickled out as you unlock new parts of the room. Progressing in the investigation unlocks rewards for the radio station, like bonus collectables in a video game. If in doubt: copy from video games. They’ve been doing this longer than we have. But then there was also the small issue of us putting Radio Nowhere in the same room as Max Sinclair. We’d originally wanted to build a very similar noir mystery, so we could effortlessly swap between the two, but now we were building a completely different game with its own identity. Difficult.One bonus we had was that we were moving to a new venue, and had to tear down and rebuild Max Sinclair anyway. We were able to outfit Max 2.0 with things that could be easily turned into a radio station, like a big curved desk and extra cupboards that could be hidden under tablecloths. Posters mounted on the wall were instead hung up on chains that could be easily swapped out, and a removable curtain/coat rail was added to cover up sections of the game with ease. Even though it was months before we started working on Radio, we knew this would be happening eventually, so planned ahead with the build of Max 2.0.An early, rough sketch of how we might fit two games in one room. The thick black lines are curtains that could be pulled back to reveal different parts of the room for different games. Bad idea.

Which brings us to the build of Radio Nowhere. A process that had an obvious problem: Sure, we can find ways to nestle the two games inside each other, but escape room builds take months… and Max Sinclair is still open to customers.So we built a facsimile of the game in an empty room next door. We arranged tables in the rough arrangement that they’d be in, and did our best to plot out the gameplay elements. Props, lock boxes, and radio equipment were assembled here, and we continued our “Test Often” approach while we built this fake version of the room.Fake escape room!

Without the actual lighting or any sort of sound system, it felt pretty lifeless, but this turned out to be important. For a game that relies so much on atmosphere and vibes, testing in a dry and lifeless room meant that we could make sure that the core of the game was fun. We built that foundation until it was strong, then added everything else on top.That worked nicely for a month or two, until we eventually needed to put it in the actual space, and test it into oblivion with the real lights and sound. But we still had bookings for Max Sinclair! So we had to build the radio station, run the tests, and then dismantle it again to put Max back together. There were an exhausting couple weeks where we were building and rebuilding each room every other day.Ahh, that’s better.

In an ideal world, we would have closed shop for the week or two leading up to launch, but we weren’t quick enough on the trigger and had pre-existing bookings right up until launch day.But launch day came and everything, miraculously, went well. It was a hell of a trial to get here, with twists and turns and failures along the way. The first thought of a new game came about a year before it opened, with proper planning about 6 months out, and serious building for about 4 months leading up to launch. The game’s been a big hit, and so far everyone’s been loving it. We’ve had a lot of people say they prefer it to the original game, and even had one player tell us that we’re “Creating a new genre”. Phew. I guess we pulled it off. Second album syndrome: AVOIDED.