How to Build Scotland’s Best Escape Room for Less Than £2k.

April 2024 - Ronan Jennings(This is very long, but it’s separated into chapters that are listed below, so feel free to jump around to the bits that interest you)At the time of writing this, The Murder of Max Sinclair (formerly just called Case Closed), has just been awarded ‘Best in Scotland’, in the Escape the Review Players’ Choice Awards. This is super exciting, and we’re absolutely thrilled. We were up against some really cracking rooms at Escape the Past, Locked in Edinburgh, and Locked in Glasgow, all rooms that I’m a big fan of. Well done to all of these places.But something that makes us very different to these games is our budget. I don’t know any exact numbers for these games, but the average budget of escape rooms in the UK is somewhere between £30,000 and £50,000.We built the Murder of Max Sinclair for £1,800.Nick Moran (creator of Time Run, Phantom Peak, and all round maker of cool things (Nick if you’re reading this, let’s be friends)) said in an interview with the Cipherdelic podcast last year that “Eight years ago, you used to be able to make a cheap room for only twenty grand.” Nick goes on to say that customers are getting used to the novelty of escape rooms, and the only way to keep up with their expectations is to build bigger and crazier rooms in a way that pushes the budget into the hundreds of thousands of pounds.I’m going to lay out how to do things differently. There are two main angles of this. The first is that bigger does not necessarily mean better. Or rather, bigger isn’t the only way to be better. Nick’s right, the public are getting tired of normal escape rooms. But that doesn’t mean the only way to give them an exciting experience is to build an eighteen-room game with half-million pound robotic pistons controlling the walls (though that would be awesome). It just means they want something different.

So I suggest you change up the style of gameplay. Change how the player feels in the room, and change what you’re asking them to do. In our games, we largely forgo the classic puzzle/lock dynamic, and instead ask players to solve mysteries, piece together bits of evidence, get into character, and occasionally run a fake radio show.The way we pull this off is by giving players “police paperwork” to fill out, where they write down their theories and answer specific questions about what they’re finding in the room. We got some nice paper (£16 for a big pack), some manilla envelopes (£10 for a pack), and stuck a letterbox in the walls (£10). Players work through the case, write down their theories, and post them off for review. It’s a completely different style of gameplay that feels like you’re doing real detective work, and we did it for £36. From that point on, regardless of what the rest of the game is like, it’s already a unique experience.

I’m not going to go too deep into this here, because I talk about how to turn escape rooms into live action video games in another article, but think how you can give players an experience that’s unlike what they’ve done before, instead of just being a BIGGER version of what they’ve already seen.That’s one side of the coin. The other side is the actual practical economics of the build, and that’s what we’re going to be digging into.Let’s break it down into a few categories, starting broad and then getting more specific:

Be creative with the space available to you.Picking your theme sensibly.Begging, stealing, and getting a helping hand.Spending the money where it counts.Smoke and mirrors, building tech for cheap.

These first couple categories are going to be quite broad. These are the things to think about before you start your actual build, ways to slice the budget in half before you even get started.

1. Be Creative With The Space Available To You.First up we have the weird stuff. This is going to be situationally specific, and not necessarily applicable to everyone. But before you even start building or planning a room, think to yourself if there’s any way you can break away from the obvious plan, and use your available space in a more efficient and creative way.For our new game, Radio Nowhere (also a budget of around £2k), we didn’t build an entirely new space to hold the game in. We instead built it in, on, and around The Murder of Max Sinclair. The two games are nestled inside each other in the very same room, and we can swap back and forth between them in the space of about an hour or so. We’ll be running each game for a week before swapping over to the other. The specifics of how we did this are worth a whole article on their own, but this meant that we didn’t need to bother about painting the walls for Radio Nowhere, or buying furniture, or hooking up cameras and microphones, or figuring out how cables will reach to our control room, because all of that had been done already. Radio Nowhere uses the framework of The Murder of Max Sinclair, but rearranged into a completely different experience. This also means that going forward, we can have double the number of games in rotation as we have rooms available.With the very first version of Max Sinclair, we managed to haggle a tiny 3 by 3 metre attic office space above an axe throwing range to host the game in. It was tiny and almost unusable, but we got it essentially for free. So we gave that tiny space as much character and atmosphere as we possibly could with the help of remote colour-changing lights, atmospheric music, and moody voiceovers, until its size became almost irrelevant. The game has points where the lights go out, the story moves into a new chapter, and you get access to all sorts of new toys. It’s the experience of entering a new room, but you haven’t gone anywhere.The room we started with for our original game. Challenge: turn this into an award winning escape room.

So before you start your build and construct a whole physical room from scratch, see if there’s anything weird you can do. Improvise creatively with the space you have, and you might just be able to save yourself an awful lot of money.

2. Picking Your Theme SensiblyThe last thing before you kick off the actual construction is to pick the theme itself. You’re going to need to be sensible about this. Think about the fantasy you’re trying to deliver, and build something you can actually make.If you’re planning to make a spaceship, then that’s obviously going to cost a lot of money. If you’re filling the place with computers, interfaces, crazy tech, and interior design that turns a dusty old office into the bridge of a star cruiser, then you’re going to be spending quite a bit.But if you’re making a detective story that’s canonically set in a dusty old office, then your set comes almost pre-made. The work’s been done for you.

The same space a few weeks later. With just a lick of paint and some coloured lights, the decoration’s almost complete.

One of our early (very early) ideas for Case Closed was to make a vaguely Alien vs Predator themed experience, where an archaeological expedition has a sci-fi horror twist half way through. That was a terrible idea. We decided to keep the dusty old office and save ourselves many, many thousands of pounds.

3. Begging, Stealing, and Getting a Helping HandWith the framework set and the game planned, it’s time for the actual build. And the first piece of advice here is one that feels obvious: Get as much as you can for cheap, if not free.You need a nice, fancy briefcase that’s probably going for £100? See if there’s one on Ebay for £20, there probably is. If you’re looking for something, then find it for cheap. But also let yourself be guided by what you can get for free, even if it wasn’t part of the original plan. Build the game around the resources you have, and learn from the Robert Rodriguez school of film making.When we moved into our original venue, we had no money for furniture, but there were a couple filing cabinets kicking around, totally unused. Did I have a plan for filing cabinets in the room? Nope. Did the room now feature two filing cabinets? You bet.The axe-throwing venue we were based above had a laser-pointer distance measurer they weren’t using? Cool, it’s now a puzzle device used for calculating bullet trajectories. This applies to people as well. Of course, pay appropriately where you can, and don’t you dare exploit anyone, but if you’ve got friends who are excited about your new project, and you treat people with respect, often people are willing to just help out. They can be extra pairs of hands for moving and painting, but can also lend more specialist skills, like voice-acting and sound design. When you’re making something exciting, sometimes people are excited to just be involved, so long as you’re nice.Bribe people with doughnuts, and you can recruit an army.

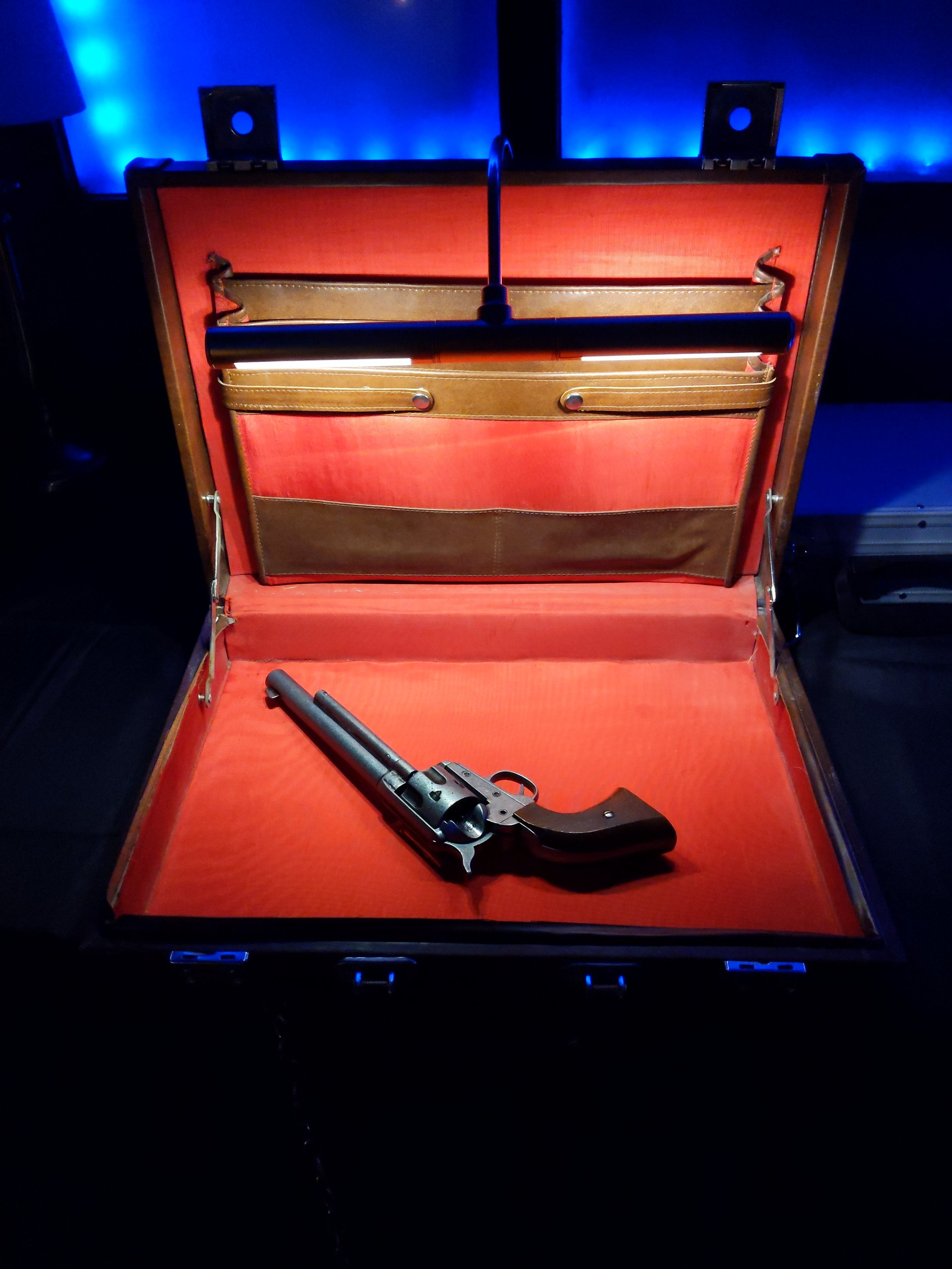

Again: Pay people well wherever you can. But sometimes calling in a favour or just letting someone make a cool thing for fun is the way to go, and saves you from spending a fortune on professionals. 4. Spending the Money Where it CountsNow this is where things get a little more specific. You’re building your game, and you’ve only got a certain amount of cash available for your props and decoration, so you need to spend the money where it matters most. At this point you have to ask yourself “What parts of this game are the most important to the experience? What NEEDS to feel real?”. These are the bits that, okay, you might need to splash out on a little bit. But splash out correctly, and you’ll be able to save yourself hundreds of pounds on everything else.To give you an example, the Murder of Max Sinclair features guns. Really nice, high-quality replicas of Colt .45 Peacemaker Revolvers. They’re metal, weighty, and feel real in your hands. The hammer can pull back with a satisfying click, the loading cylinder spins, and you can actually load dummy bullets into it. It really feels like you’re handling real firearms (Yes, this is legal, we’ve checked). They cost between £60 and £80 each, and so we spent about £250 in total on fake guns. It was probably the biggest single expense of the original game, but it was well worth it. GUN!

We built a puzzle around these guns where you need to identify their manufacturer and model types, but this required a lot of other elements outside of the guns themselves, like reference guides for different gun manufacturers, and ways to measure the weights and barrel lengths of each one. That £250 wasn’t going to be the only money spent on this puzzle…Except that the reference guide is 3 pieces of paper I printed off and stuck in a £2 binder from WHSmiths. The weight is measured with some £10 kitchen scales from Amazon, and you can find the barrel length with an old ruler we just had kicking around. The price of these things is basically negligible, and the production value is zero. But none of that matters when you’re holding what’s essentially an ACTUAL REAL GUN.We could have professionally printed a period appropriate firearms manual that accurately reflects the style and design of similar things in the year that the game is set, printed on high quality material, but… why? Nobody would notice, or care, because they’re HOLDING A GUN. That’s where all of their attention is.Another example is the forms that the players write their theories on in Max Sinclair. These are the centrepiece of the game, that every other puzzle eventually comes back to, so they had to feel good.I spent a long time designing the forms to look and feel like real police forms. We bought the nicest textured paper we could find, and got some high quality inky pens to write with. It feels like you’re writing an old fashioned letter, or writing genuine detective’s notes, and it adds a lot of weight and authenticity to the answers you’re putting down.Contrast this even with Radio Nowhere, which uses the same form and envelope system. Sure, you’re writing your answers and posting them off in the same way, but the forms themselves are less crucial to the actual experience. In Max Sinclair the forms are diegetic, existing in the world of the story. The people who are reviewing them are characters in the story, and the act of the notes being passed back and forth plays an important role in the narrative.That’s just not the case in Radio, the game is about different things. Sure, I had some fun and designed them in bright and colourful ways and gave a lot of character to each one, but it wasn’t so integral to the experience that they felt real, so we laminated them and gave the players marker pens. It doesn’t feel as good, but in this game it doesn’t need to feel as good. There are other things that are more important. The focal point is elsewhere.

Figure out what actually matters and what’s core to the experience, and make sure THAT is good. Everything else can be scraps of paper and laminated cards and whatever you like, so long as it doesn’t distract from what the players are likely to actually care about. Find the bits that hold the rest of the game up, and give them your love, attention, and budget, because that’s what people will remember.

5. Smoke and Mirrors, Building Tech for CheapThis last section is about something that’s often the biggest money-sink for any escape room build: The tech. Or, as we do it at Case Closed: Smoke and Mirrors. Essentially, if there’s a way to create the effect of whatever tech you’re trying to build without having to actually build something that’s fully functioning, then that’s what we do.There’s two main ways we pull this off:First, there’s the big cheat. Which is, of course, to completely fake it. These are points where the players do something in the room that feels like it’s doing something, but is actually just a cue for the GM to press a button. This is a touchy subject, as players don’t like feeling like they’re being guided through an experience they’re not in control of. They want things to be real. So this tactic needs to be used sparingly, and disguised carefully.

One example of this in Radio Nowhere (only slight spoilers) is where players find a hidden floppy disk, labelled “TOP SECRET”. They insert this floppy disk into a big 90s computer tower, and a mysterious garbled message plays through the speakers, which they can unscramble using some radio equipment.Getting the floppy to genuinely hold the audio file, having the 30 year old computer work as it’s actually supposed to, and having them both interface with a modern MIDI audio controller would be, frankly, an absolute pain in the ass. Getting this to work reliably every time would be almost impossible. So, of course, the floppy disk is completely empty, the computer tower isn’t plugged in, and the audio plays from a completely different source when the GM presses a button.But this works for a couple different reasons. Mainly, there’s a few genuinely real things going on. Sure, the floppy disk doesn’t actually play the music, but the equipment they’re using to unscramble the message does work. They’re actually listening to live audio, and really adjusting the levels, pitch, and volume in real time. That’s the important part, the floppy disk is just a fun way to build up to it.Also, it just feels good. Floppy disks are nice to hold, you find this one hidden somewhere satisfying, and have to do a bit of tactile fennangling to reach it. It slides into the computer tower with a satisfying click, and has a spring loaded eject feature that shoots the disk out with a clunk when you press the button.Plus, people just like seeing floppy disks. Nostalgia works wonders.So long as it feels good to do, is a nice treat for players to play with, and leads up to something else that genuinely works the way we’re presenting it, it doesn’t matter that the floppy disk is completely blank. Usually the players don’t even notice, but even when they do, it doesn’t bother them. We’ve created the space for them to have fun, and they’re more than happy to suspend their disbelief and just play along.The other side of our smoke and mirrors act is with the tech that does actually work. And we do that by making it work just enough. Where a bigger company might custom order some high tech device that has lights and sounds and does exactly what they want, we’ll figure out what effect we’re trying to convey, and cobble that together from whatever we can scavenge. The best example of this is the actual radio station part of Radio Nowhere. We wanted to make the players feel like they were in charge of a real station, but didn’t have a lot of cash to burn.

Having a fully functioning radio station was one of those ideas that started off a joke because it’s -at first glance- entirely unreasonable, but we pulled it off in an alarmingly simple way. We got a cassette player (£30), and plugged it into one of those FM transmitters you used to use to listen to your iPod music in the car (£10). This broadcasts to a radio (£20) on the other side of the room. No cables, genuine broadcasting. We got the cheapest microphone we could find (£10), grabbed some spare headphones we had lying around, and bought one of those LED scanner light displays you might see in the back of a New York Taxi Cab (£35). Done.Any cassette tape the players stick in the player broadcasts and plays on the radio, which can be turned up and down and tuned to different frequencies. Anyone who speaks into the microphone will hear themselves played back in real time through the headphones. To top it all off, the LED display can change to any message we type, so the players get compliments on their music taste, occasional requests for news or specific songs, and a “live” counter of their listener numbers, which goes up and down based on how entertaining they’re being on the mic.It might not hold up under full scrutiny by an actual radio professional, but as a backdrop and playground for a team of people who are also trying to solve a murder, it does the job pretty damn well. And it cost about £105 in total. Probably our biggest single expense for that game, but a damn lot cheaper than the thousands it would have cost to have a professional team build and rig up a custom device and interface for us. Don’t let over-designing be your downfall.The radio station in progress. It looks a lot fancier in the final product, but these are the bones! It doesn’t take much more than this.

Between all of those tricks, we’ve been able to keep both of our room budgets so far in the vicinity of £2,000. This means we can experiment, take risks, and build things that are out of the ordinary, because we haven’t poured our life savings and a year’s worth of income into each one. If a game didn’t click with the public, it’d be a shame, but it wouldn’t bankrupt us. It also means we can build new games more frequently, as we’re not waiting for years to recoup on previous investments. I’m writing this two weeks after the opening of Radio Nowhere, and it’s almost already broken even.Don’t pour all the money in the world into your games. Think about the experience you’re trying to create, and think about how most efficiently to create that. Bigger doesn’t necessarily mean better, so think differently, think weirdly, and innovate in how your operation works behind the scenes. Spend the money where it counts, fake the things you can, and improvise the things you can’t. I want to see more weird and unusual games out there, and that’ll never happen if they’re all enormous financial gambles.Get cheap, get weird, and make something fun.